UNTIL THAT STRANGE SCENE IN 1993, no one had ever taken the Leadville Trail 100 ultramarathon lightly. Leadville forces racers to run and climb 100 high-altitude miles over the scrabbly trails and snowy peaks of the Colorado Rockies. You don’t train for Leadville with intervals and striders; you train the way a prison gang handles a rock pile, by constantly banging out lots of slow, steady miles and building the kind of thin-air endurance that lets you grind along at 15 minutes a mile all day long and then continue into the night. The Leadville ultra, you could say, is closer to mountaineering than marathoning.

But there, next to the carefully pulse-monitored and Polar-Fleeced top seeds at the 1993 starting line, were a half-dozen middle-aged guys in togas, smoking butts and shooting the breeze, deciding whether they should wear some new Rockport cross-trainers they’d been given earlier or the sandals they’d made out of old tires scavenged from a nearby junkyard. Most opted for the sandals. They weren’t stretching or warming up or showing the faintest sign that they were about to start one of the most grueling ultramarathons in the world.

They were Tarahumara Indians from the Copper Canyons region of northwestern Mexico. Their curious appearance matched their mysterious legend—that they defy every known rule of physical conditioning and still speed along for hundreds of miles. The Tarahumara (pronounced Spanish-style, taramara by swallowing the “hu”) didn’t work out, or stretch, or protect their feet. They chain-smoked fierce black tobacco, ate a ton of carbs and barely any meat, and chugged so much cactus moonshine that they were either drunk or hungover an estimated one-third of each year (one day on their backs, that is, for every two on their feet). “Drunkenness is a matter of pride, not of shame,” Dick and Mary Lutz wrote in their book The Running Indians. And yet, the Lutzes insist, “There is no doubt they are the best runners in the world.”

Leadville was sure to test that claim. Once the starting gun sounded, around 4 a.m., a sea of taller heads quickly swallowed the Tarahumara runners, who faded into the middle of the pack behind the world’s most scientifically trained ultrarunners. As the sun rose, though, and the course began climbing toward the 12,640-foot peak at Hope Pass, the Tarahumara began easing forward, running so beautifully that one Leadville veteran was left mesmerized. “They seemed to move with the ground,” Henry Dupre would later tell The New York Times. “Kind of like a cloud or a fog moving across the mountains.”

At the first aid station, the Tarahumara who had decided to try the Rockports were now shucking them and pulling on the trash-picked sandals. By the turnaround point, sandaled feet were pattering hard behind the leaders. Not only were the Tarahumara gaining, but they also seemed to be getting stronger: They weren’t picking off the faders, so much as picking up the pace. Reports from observers at mountaintop stations said the Tarahumara were even smiling as they passed. Joe Vigil, the legendary American track coach, happened to be at the Leadville 100 that year, and he couldn’t believe what he was seeing. “Such a sense of joy,” Vigil would later say.

As the lead runners came to the finish, the Tarahumara had added reason to be happy. Breaking the tape, in a time of 20:03:33, was 55-year-old Victoriano Churro, a farmer and the oldest of the three Tarahumara. He was followed by Cerrildo Chacarito in second and Manuel Luna in fifth. The three Tarahumara were still bouncing along on their toes as they crossed the line.

Their performance proved to be no fluke. A year later, another Tarahumara runner, Juan Herrera, would win at Leadville, finishing in 17:30:42 and chopping 25 minutes off the course record. Then in 1995, three Tarahumara finished in the top-10 of the rugged Western States 100 in California.

How did they do it? Before anyone could find out, the Tarahumara vanished from the ultrarunning scene in the mid-’90s, retreating to their canyon-bottom homes, and taking their miraculous distance-running secrets with them.

One runner, it was said, set out after them.

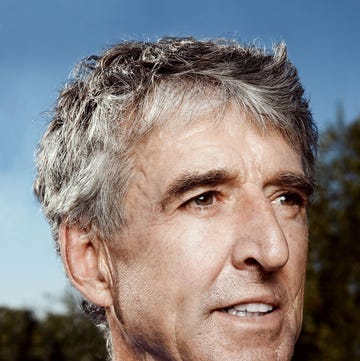

HE’S SUPPOSED TO BE AS TALL AS SASQUATCH and speak a raucous, gibber-gabber tongue that’s neither Spanish, nor English, nor Tarahumara. The Tarahumara call him Caballo Blanco—the White Horse—because every once in a while, the villagers say, he will come galloping down from the hills, stomping his feet and snorting like a runaway stallion. He has an invisible sidekick he’s always talking about, an Apache warrior he claims is an even greater runner than the Tarahumara and whom he says is called Ramón Chingón (which, if you throw in a certain expletive, means the opposite of “everybody loves Raymond”).

He’ll be invited to gulp a cup of piñole, a traditional Tarahumara dish of ground corn mixed with water, and then bound back up the trail with his quick, billy-goat gait, a parade of kids laughing and trailing behind. “Caballo Blanco és muy amigable,” the villagers say, “pero un poco exquisito.” The White Horse is a good guy, in other words, if you like ‘em goofy. But if any outsider has mastered the Tarahumara secrets of long-distance running, they agree, it’s Caballo Blanco.

No one seems to know Caballo Blanco’s name, or age, or nationality. Some say he’s American; others, German; still others, Dutch. He came to Mexico years ago, the story goes, and wandered deep down into the wild, impenetrable Barrancas del Cobre—the Copper Canyons—to live among the Tarahumara.

For two days I’ve been searching Mexico’s Sierra Madre Mountains for the phantom runner, and the search has finally brought me here, to the dark lobby of an old hotel in the dusty town of Creel, hard by a stretch of railroad tracks and hundreds of miles across the desert from Chihuahua where we started.

“Sí, he’s staying here,” says the desk clerk.

“Really?” After hearing we’d just missed him so many times, in so many places, I’d started to suspect Caballo Blanco was a ghost story, a Loch Ness monstruo dreamed up to yank the crank of gullible gringos.

“And he’s always back by 5,” she adds.

It’s almost too good to be true. Then, I check my watch. “But it’s already after 6.”

The clerk shrugs. “Maybe he’s gone away for a few days.”

I slump down on a lumpy sofa. I’m exhausted, and as I doze I can almost hear his voice. Then it hits me: I am hearing it. My eyes pop open, and I see a boney, blonde gringo in trail-wrecked Tevas and a floppy jungle hat bantering with the desk clerk.

I erupt from the sofa. “Caballo?” I call out, my throat still sleep-clogged. He turns toward me. “Damn, am I glad to see you!” I explode, scaring the wits out of him. Once I reassure him that I’m not a cop, a con man, or a deadbeat American looking for a handout, Caballo Blanco beams a big, toothy grin.

“Sure,” he says. “I’ll tell you about the Tarahumara. But first, let’s get some beans.”

We walk to a tiny, backstreet restaurant, a single room with two rickety tables at arm’s reach from an ancient gas stove where a deliciously fragrant pot of frijoles is bubbling. As we stoop through the doorway, we see an old woman with a wooden spoon. Immediately, she calls out, “Hola, Caballo.”

“Como está, Mamá?” Caballo Blanco shouts back. He’s got “mamás” all over Latin America, he says: motherly women who fill him up with beans and tortillas for only a few centavos, so he doesn’t have to worry much about money and can concentrate all his time and energy on running instead.

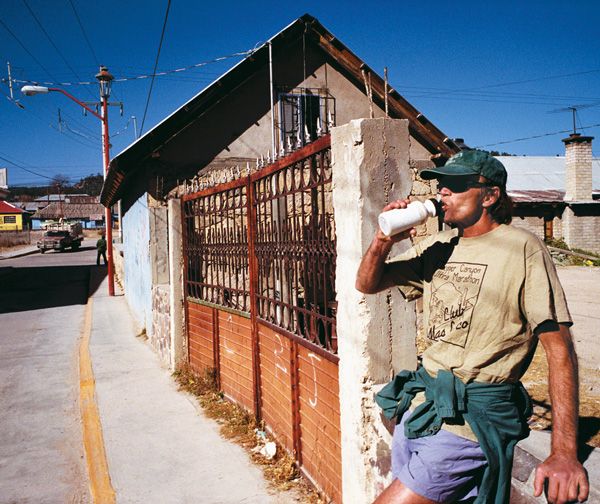

His name, he says, is Micah True (though he would later tell me he was born Michael Randall Hickman and renamed himself for the Biblical denouncer of decadent living). He lives in a simple shack in the old mining town of Batopilas, close to the hidden canyon homes of his Tarahumara running buddies. He’s tall, sandy-blond, and Nordic-ly toothy, which partly accounts for the confusion about his nationality; that, plus the fact that he’s from Nederland, Colorado, and has an atrociously tin ear—even after 10 years in Mexico, his Spanish would make a Berlitz teacher wince. He’s 51, but likes to suggest he’s older, probably because he knows he looks it; feats of endurance under an unforgiving sun have left Caballo a little on the skeletal side.

“I came to running late…” Caballo begins, but suddenly stops, bug-eyed with hunger, as Mamá plops several big bowls in front of us and futzes over them with chopped cilantro, jalapeños, and squirts of lime. Caballo hasn’t eaten all day. He’d set out this morning with a friend for a short hike to a natural thermal spring in the woods, but once he spotted an unfamiliar trail through the trees, hike and hot tub were history. He took off running, with no clue where the trail was taking him. “I wasn’t even going to run today, but I was loving it,” he says. An hour or so later, he found a trail linking back to town, turning what should have been a relaxing soak into a half marathon.

That’s one of the first and most important things he learned from the Tarahumara, Caballo explains between spoonfuls of beans: the ability to break into a run anytime, like kids in the schoolyard. “Look,” Caballo says, pointing first to his waist, then to his feet. He’s wearing ancient hiking shorts to go along with his dumpster-ready pair of Tevas. “That’s all I wear.” When he sets out for a 20-mile run, he’s no more equipped than any Tarahumara hunter: just shorts, sandals, and a bag of piñole.

“It’s a beautiful thing,” Caballo says and smiles. “And I’m still just learning.” Imagine learning hoops by playing with Bird, Magic, and Jordan every day, he says. That’s what it’s like running with the Tarahumara. Not even the best Kenyans have figured out what the Tarahumara know, Caballo swears; the Kenyans may be faster over the short haul, but few runners can handle more miles, for more years, than the Tarahumara. In fact, Tarahumara runners have competed for Mexico in the Olympic Marathon twice (in 1928 and 1968) and both times finished deep in the pack. Afterwards, they complained that the race was too short.

“As a culture, they’re one of the great unsolved mysteries,” chips in Danny Noveck, who has joined us at the table. Noveck is a pal of Caballo’s and a University of Chicago anthropologist now researching the Tarahumara culture. “Here’s an example,” he says, waving a can of Tecate in the air. “The Tarahumara have a beer-based economy, yet somehow it works.” Instead of cash, they like to trade in home-brewed corn beer, called tesguino, which inevitably leads to a good amount of inebriation in the name of commerce. “But they’re also extremely hard workers,” Noveck says.

The Tarahumara, it seems, just farm and party and run for fun, all the while staying in remarkable condition. In 1971, physiologist Dale Groom ran cardiovascular tests on Tarahumara adults and children, and concluded (as he’d write in the American Heart Journal), “Probably not since the days of the ancient Spartans has a people achieved such a high state of physical conditioning.” Groom checked the pulse and blood pressure of Tarahumara runners during a five-hour race, and found their blood pressure went down while running, and their average heart rate—in the midst of banging out eight-minute miles—was only 130 beats per minute. But what most impressed Groom was something that didn’t register on his instruments: After running 50 miles, the Tarahumara didn’t even look beat. They stood around and chatted while Groom pumped the diastolic cuff.

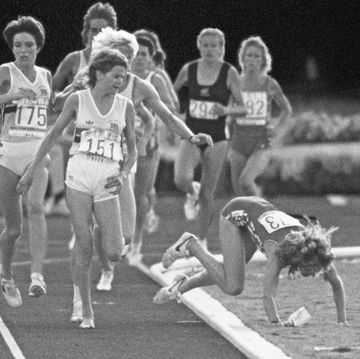

During his years at Adams State College in Alamosa, Colorado, Joe Vigil coached 19 national championship teams. He also earned three advanced degrees. But nothing he’d seen on the track or in his physiology books left him prepared for what he witnessed at Leadville in 1993. The harder the Tarahumara fought their way through the Rockies, Vigil marveled, the more rapturous they became. Glee and determination are usually antithetical emotions, yet the Tarahumara were brimming with both at once; it was as if running to the death made them feel more alive. ”It was quite remarkable,” Vigil now says.

Heart disease, high blood pressure, and lethal cholesterol are virtually unknown among the Tarahumara, Vigil would later learn. So are crime, child abuse, and domestic violence. Seekers used to climb the Himalayas to discover the secret of a serene, hyper-healthy life; Vigil now realized it lay just south of the United States border. So after retiring in 2000, Vigil and his wife sold their home in Colorado, intending to spend the next few years studying the Tarahumara. But just before they were to leave, Vigil got a phone call. Actually several of them. A bunch of U.S. elite runners, among them Deena Kastor, were begging Vigil to stick around and train them for the 2004 Olympic Games. How could he say no?

In 1994, Micah True had his own encounter with the Tarahumara at Leadville. He’d heard about their incredible performance the year before and wanted to see them in action for himself. But instead of competing against them (True already had run a few Leadvilles), he offered himself as a guide. He teamed up with a Tarahumara runner over the back half of the course, he says, and “we spent the next 10 hours together, and even though we didn’t have much language between us, somehow we could joke and communicate.” After the race, he was as obsessed as Vigil with learning the Tarahumara secrets, but unlike the coach, nothing anchored True to Colorado but a ‘69 Chevy pickup and a one-man landscaping business.

“I have no wife, no kids, no expenses,” Caballo says, as he mops up the last of his frijoles with a scrap of tortilla. But the tricky part, he learned, would be gaining access. The Tarahumara, for very good reason, refer to most outsiders as “white devils.” They may let researchers monitor their hearts, but not look into them.

“I did have one thing working for me,” True says. “When you act out of love, good things happen. It’s a law.” He’ll finish the story tomorrow, he says, when we meet for a run. But he leaves me with this thought: For centuries, whenever outsiders have tried to get close to the Tarahumara, they’ve responded by running. Away.

SO WHERE THE HELL ARE THEY? A few days before meeting Caballo Blanco, we were out here in…in…actually, I really didn’t know where we were anymore. Salvador Holquín, a 33-year-old, semipro mariachi singer doubling as my driver, had been grinding and rocking his Dodge Ram truck in low, low gear since dawn, wheezing like a tramp steamer on stormy seas, trying to squeeze through logging trails so narrow that the passenger-side wheels were closer to the cliff’s edge than I cared to look. I tried keeping track of our location with a compass and forest map, but my head was throbbing from smacking the roll bar every time we jounced to the axles on a rut, not to mention Holquín’s relentlessly ay-yay-yay-ing mariachi tapes.

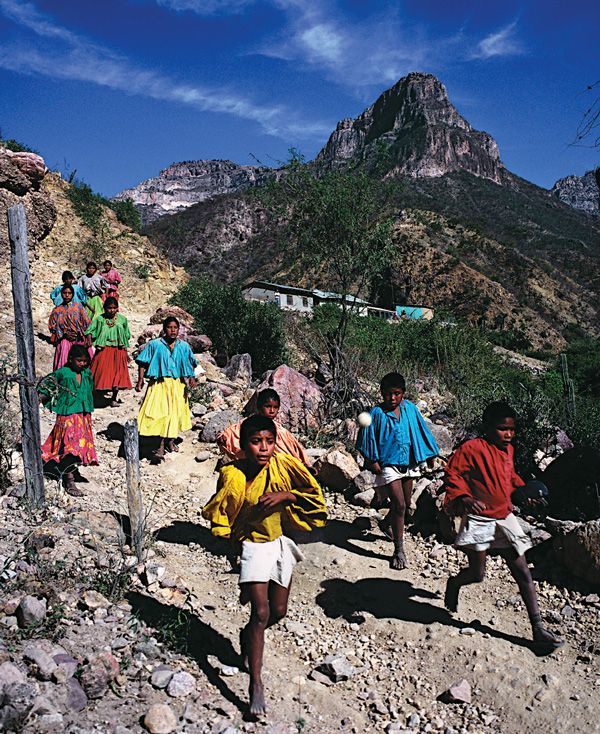

Somewhere out here are the hidden canyon homes of the Tarahumara, though the Tarahumara might quibble with one detail. They call themselves Rarámuri—the lightning-footed people. “Tarahumara” is the garbseled name they were given by 17th-century explorers who didn’t understand the tribal tongue. The name stuck, ironically, because the Rarámuri remained true to it by running away instead of hanging around to argue the point.

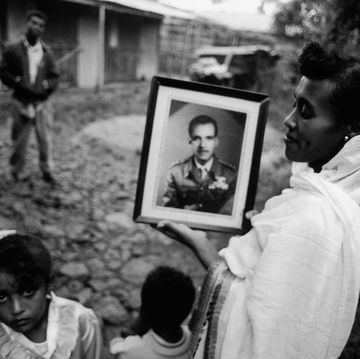

That has always been their way. Ever since Cortez’s armored conquistadors came jangling into their homeland, and lasting through subsequent invasions by Mexican homesteaders, Pancho Villa’s roughriders, and U.S.-backed timber barons, the Tarahumara have responded to centuries of blunderbusses, bulldozers, and Kalashnikovs by simply avoiding them, retreating deeper and deeper into the labyrinthine Copper Canyons.

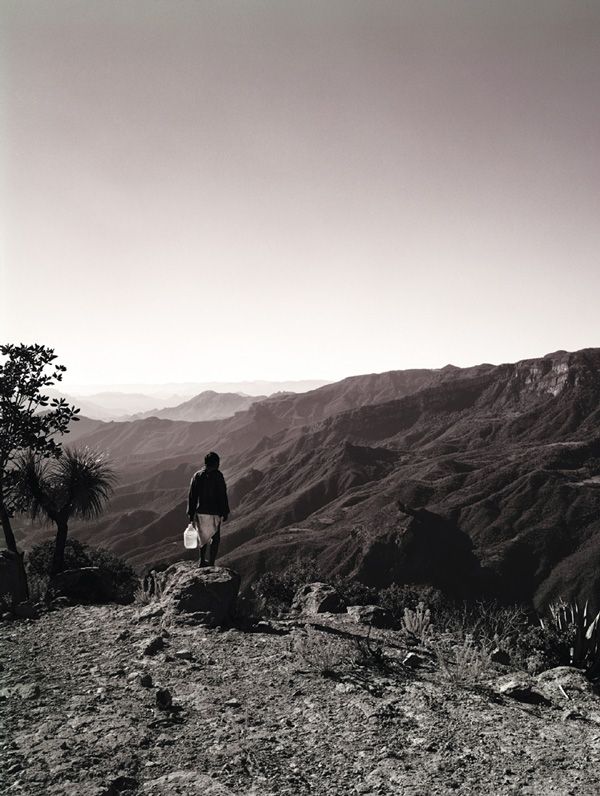

It’s left them, today, one of the most remote people on the planet. Fewer than 40,000 Tarahumara remain, from a population of 2 million a century ago. No wheeled vehicles can make it to the bottom of the Copper Canyons, and few choppers would try: The gorges are a twisting maze of swirling drafts and sheer rock walls, many plunging deeper than the Grand Canyon. Only hooves and seriously determined legs can make it much farther than where we’d come to: the far end of a pathless forest, above Tarahumara huts and cave dwellings some 8,000 feet below.

We’d set out at noon yesterday from Chihuahua, driving southwest across the desert. Holquín had a general idea of the area, since he also helps recruit Tarahumara runners for the Ultramaratón de los Cañones, a 100-kilometer trail run through the Sinforosa Canyons each July. The Canyon Ultra, as it’s known, is something of a cult attraction for the cognoscente who idolize the Tarahumara, since it’s one of the very few organized races they still run.

The defending champ is Arnulfo Quimare, a 24-year-old Tarahumara who may be the greatest runner you’ve never heard of. For the past three years, Quimare has defeated all comers. What’s more, he took the title from his brother and has been defending it against his brother-in-law, which means that somewhere in the Copper Canyons, invisible to the outside world, a distance-running dynasty is forming.

“We nearly there?” I asked Holquín, once the road had narrowed nearly to the point of disappearing.

By way of answer, Holquín backed up, cut a hard right off the road, and started winding between the trees. We wandered like this for an hour, and then, as the sun set, we emerged from the woods to see three men silhouetted against the edge of a gigantic canyon. We pulled up next to them, stopped, and got out.

I’d rarely been in such an eerily silent spot in my life; there wasn’t even a rustling branch to break the silence, yet I could still barely hear the one Tarahumara who responded when Holquín pulled up and said “Cuida va”—Tarahumara for “How’s it going?”

“Cuida,” the Tarahumara breathed, soft as a sigh.

The other two didn’t say a word. All three were dressed in homemade huaraches and one-piece tunics that hung short in the front and ing in a long, triangular tail behind. The greetings over, we all stood in silence for a while, gazing at the spectacular molten sunset receding from the far canyon wall.

Soon, a battered Jeep appeared, and another Tarahumara slid from the driver’s seat. “Silvino,” he introduced himself, shaking hands shyly with just his fingertips. Unlike the others, he was dressed in work pants and Reebok sneakers. Last year, Silvino said, the Christian brother who runs the Tarahumara school drove him to Mexicali, where he says a marathon offered a $10,000 first prize. Silvino won, and split the pot: Half the money went to the school, the other paid for Silvino’s new ride and duds.

“What was your winning time?” I asked.

Silvino spat into the dust. “No me acuerdo” (I don’t remember).

“Will you race it again this year?”

He loogied again. “Maybe. If the brother wants to go, perhaps…”

However, Silvino perked up when he heard we were interested in meeting Arnulfo Quimare. Every year, Silvino races the Canyon Ultra, and every year, he finishes behind a member of the Quimare clan. He says he wants a rematch, but not in some dull trail race, which Silvino somehow finds simultaneously too short and too boring. He prefers an all-out rarajipari, the traditional Tarahumara ball race. One village will send word that it’s ready for a challenge; when a rival village responds, they’ll set a time, place, and distance. Three or four runners usually compete from each village, but Silvino knows of rarajiparis that fielded 10 per side.

The night before a race, the two villages get together to drink and bet. Early the following morning, the teams line up on a stretch of trail about five miles long, unless the runners got too drunk the previous night and decided to call off the race, as occasionally happens. The Tarahumara’s taste for corn beer, by the way, is not some form of aboriginal alcoholism, as anthropologist John Kennedy explains in Tarahumara of the Sierra Madre: Beer, Ecology and Social Organization. It’s actually a clever cultural defense mechanism for a tribe that has powerful emotions and no refrigeration. Because the Tarahumara are often too bashful to act on passion, and too nonviolent to belt some annoying neighbor in the mouth, they use regular beer parties, called tesguinadas, to simultaneously vent any built-up lust or anger, and make use of excess corn by fermenting it into beer.

So assuming the race-night tesguinada didn’t get too nuts, each team will produce a small ball, carved with a machete from the hard wood of a wuasima tree. Then they’re off…and for the next 24, or 36, or 40 straight hours, they’ll do continuous laps back and forth over the course, kicking the ball along until they reach the prearranged distance, which can be anything from 100 to 200 miles. During the night, the nonracing villagers will light the course with okote—burning pine torches—and feed the runners water and piñole.

Last year, the other two members of Silvino’s team dropped out in the middle of their rarajipari. For the rest of the night and into the next day, he raced on by himself, constantly surging and easing back to keep pace with the ricocheting ball, hunting it down when it caromed off the rocks. He was doubly lucky, Silvino says: He not only finished the 120 miles and won, but he also didn’t piss blood for the next few days, as he has in the past.

This kind of action gets Silvino fired up. It’s much more uncertain; consequently, more dramatic. No one knows in advance when the race will be, or who will show up, or how deep a crevice a ricocheting ball may need to be retrieved from in midrace, or who will take a midnight tumble and gash his head. But that’s what real running is all about, Silvino tells me; any able-bodied Tarahumara can finish an ultramarathon, but there’s no telling how anyone will fare during the long, lonely night of a rarajipari. For Silvino, it’s the difference between a guy who runs races and a guy who runs.

At dawn the next morning, one of the Tarahumara agreed to guide us to Arnulfo Quimare’s house. After a five-hour hike down a steep, faint footpath carved into the canyon by centuries of Tarahumara feet, we came to a river at the canyon bottom and picked our way upstream over the rocks. Finally, we arrived at a mud hut wedged almost invisibly against the canyon wall.

Quimare appeared in the door and blew his nose. Everyone in the family had the flu, he explained. His brother, Pedro, couldn’t even get up from the mat he was resting on. Holquín pulled me aside: Because Tarahumara families share blankets at night in one-room huts and eat from communal pots of piñole, he whispers, the flu can last for months and incubate into a serious debilitator, and often a killer. “There’s no way they’re going to be able to run with you,” he said. “He’s making a real effort just to talk.”

Quimare offered a basket of small, sweet limes and waved for us to sit. He’s tall for a Tarahumara at nearly six feet, with a Prince Valiant bob, muscle-knotted thighs, and a quiet smile. We chomped limes and spat seeds for a while, and when I started to ask about his ultra victories, that’s pretty much the response I got: chomping and spitting.

“How do you and Pedro train?” I began.

(Chomp, chomp, followed by long pause) “We don’t.”

“Don’t what—train together?”

“No [chomp, chomp, pause]…we don’t train.”

“Did you have a time you were going for?”

“No…I was just trying to pass whoever was in front of me.”

Quimare was hospitable and considered his answers carefully, if only to come up with a good one so I’d stop asking and clear out so he could rest, but as Caballo Blanco had learned years before, the Tarahumara allow white devils to penetrate only so far. Beyond that…silence.

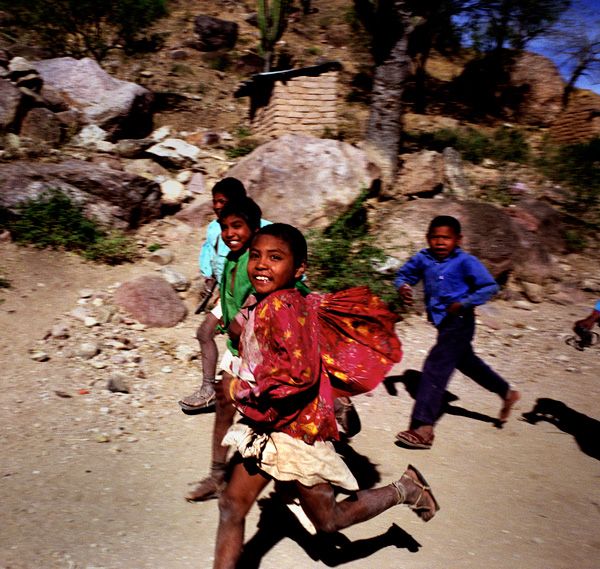

Eventually, we gave up and left the Quimares to their sickbeds. But just when I thought I wouldn’t get a chance to see Tarahumara champs in action, I got an unexpected break. We’d wandered down to a little school by the river, where dozens of kids came pouring out for recess. They were dressed like their parents—the girls in long skirts, the boys in huaraches and hanging tunics—and they quickly formed two lines.

The head of the school, an uncharacteristically portly Tarahumara named Angel, appeared with two wuasima wood balls. He quickly matched the boys up by height, then did the same with the girls. He tossed a ball to each team, then shouted “Vayan!” Two kids dropped the balls and, using the tips of their toes and a deft flip-kick motion, sent them bouncing down the trail to the river. A stampede of boys broke out, while the girls hung back; they’d join after the boys had gone about a mile. The teams seemed evenly matched, but my pesos were on Marcelino, the tall, rangy kid in the red smock who’d ripped to the front.

But shortly after Marcelino had taken control of his team’s ball and was steadily opening a lead, the genius of the rarajipari became apparent: It’s endlessly and instantly self-handicapping. Because the trail was so rocky and twisty, the ball ricocheted madly, allowing the slower kids on Marcelino’s team to catch up when he checked his stride to dig it out of a crevice. Even the smallest kids got a chance to shine: Once Marcelino reached the river, he wheeled around and flipped the ball back up the trail, right to a pudgy little six-year-old who’d lost a sandal and his belt, forcing him to hop along and hold his tunic shut with one hand. Until Marcelino could catch up, Little One-Shoe was leading his team’s fast break, and loving it.

It’s like no kid’s game I’ve seen before, and every kid’s game. Everyone is trying to win, but no one really seems to care who does; the rules are simple and adjusted on the fly, and no adults are offering advice or gumming up the fun—no hockey dads at rarajipari races. The kids accelerate when they feel like it, downshift when they don’t, and catch an occasional breather under a tree before jumping back into the fray. When the girls blend in a few minutes later, running as hard and gleefully as the boys, I’m reminded that the best speed workouts of my life were logged before I ever saw a stop watch, in kick-the-can battles involving two dozen kids and connecting backyards in the summers of 1970 and ’71.

It’s been too long since I last ran like a maniac through my neighbors’ azaleas, and I’ve been paying for it in breakdowns, boredom, and fast-twitch muscle loss: Now that I see how the Tarahumara take the spontaneity and semishapelessness of kids’ play and turn it into a lifelong running tradition, their ability to stay fast into their 50s and keep their legs immune from injury makes sense. There’s a logic to the way kids play instinctively, and the Tarahumara never abandoned it.

That night, as we camped by the school, Angel told us his version of a horror story. “There’s a Tarahumara village called Mesa de Hierba Buena,” Angel begins. “Many of the best runners were from Hierba Buena. They had a very good trail that would let them cover a lot of distance in a day, much farther than you could get to from here.” The trail was so fine, in fact, that the Mexican government decided to slick it with asphalt and turn it into a road. Now that it could be supplied by truck, Hierba Buena soon had grocery stores, and in them, soda, chocolate, sugar, butter—foods the Tarahumara had rarely eaten. They developed a taste for junk food, but needed cash to buy it, so instead of working their fields, they hitched to Guachochi to work as dishwashers and day laborers.

“That was 20 years ago. Now, there are no runners in Hierba Buena. We’ll lose the Rarámuri ways,” Angel laments. “The men will stop running. The kids won’t eat the old way, just a cup of piñole at a time. It’s terrible! There are Rarámuri who don’t respect our traditions as much as El Caballo Blanco does.”

“HU!…HU!—” I’M TRYING TO SHOUT “HORSE!”, but it keeps turning into a pant. I finally get it out, catching Caballo’s ear just before he darts around an uphill bend and vanishes. My God, I’m not that out of shape, but the way Caballo is rock-hopping, he makes me look as sick as Arnulfo Quimare.

We’d set out that morning for a run in the hills behind Creel, and within minutes we’re on a rocky, pine-needled trail climbing through the woods. It’s not that Caballo is so fast; it’s just that he seems so light, flowing as smoothly over a seriously gnarly trail as an expert mountain biker on a perfectly chosen line. “My whole approach to running has changed since I’ve been here,” he says, once I catch up. “I used to have trouble with injuries, especially with my ankle tendons. Now I’m 50-ish, and they’ve gone away.”

Caballo first came to Copper Canyons in the winter after meeting the Tarahumara runner at Leadville. Before leaving, he got on a Boulder, Colorado, radio station and asked for listeners to donate old winter coats. Once he had a pickup-load, he pointed his Chevy south. He handed out his coats, but didn’t want to leave the canyons: Tarahumara women were feeding him piñole and hand-patted tortillas, and he was running each day on the most spectacular trails he’d ever seen.

But he wasn’t included in the rarajiparis, or invited when anyone ran to the canyon top. He needed a way to break through, and the lesson of Leadville came back to him—be humble, and be funny. He started joking with the Tarahumara kids, neighing and stamping his feet. For the adults, he spun wild, bawdy tales, in his barely intelligible Spanish, of Ramón Chingón, his make-believe Apache friend. He didn’t come in as the Great White Father; he was more like a goofy, sunburned cousin. He made himself fun to run with, so some of the Tarahumara began taking him along.

He stumbled badly at first, as he tried to follow the Tarahumara over rocks and scree. But he soon learned to stop relying on his long legs to keep up and, instead, mimic their short, quick steps. He chopped his long stride into thirds, pattering out three quick steps between rocks rather than one lunge. When he tripped, he didn’t flail; he’d trust his body and find himself 30 yards up the trail, still on his feet.

One thing that struck Caballo about Tarahumara men is that they still run the way they did as kids; the rarajipari, after all, is the same game they played as five-year-olds. Caballo, consequently, avoids planned routes when possible. “I’m always getting lost and having to vertical climb, water bottle between my teeth, buzzards circling overhead,” he says. Most of all, he began to acquire the confidence the Tarahumara possess beginning in childhood, their conviction that they can run until their minds decide to stop, and not their bodies. Before Silvino ran his first 150-mile rarajipari at age 16, he never had raced more than 10 miles. How did he train for a 15-fold increase? He didn’t. “I just knew I could do it,” Silvino had told me. Or then there is the 95-year-old man Caballa saw walking for five hours up the canyons. “No one told him he shouldn’t,” Caballo says, “and he never doubted he could.”

Caballo soon saw the improvement in his running. Quick-stepping over such nasty footing, he found, made him not only more nimble, but also faster; Caballo Blanco has more foot speed and resilience than Micah True ever had during his speed-work days in the U.S. “I do all my running on trails, and that’s the difference,” he explains. “I’m not battering myself by pounding and pounding over asphalt. I’ve learned to run Tarahumara-style—smooth, high-stepping, with no urgency.”

Today, Caballo may be the only American training Tarahumara-style. After their brief rocket to stardom in the mid-90s, the Tarahumara stopped coming to U.S. ultras. An American who had sponsored them got into one feud too many with race organizers, and vowed not to bring them back. The Tarahumara didn’t really care: The ultras offered little prize money, and no special prestige back home.

So now, each March and December, Caballo organizes his own race. It’s just him, a half-dozen or so Tarahumara buddies, and the rare gringo who signs on. “It’s a blast!” he raves. The whole troop hikes across the canyon, camps out, then runs 20-some miles back the next day. Those who finish are crowned with T-shirts as new members of “Club Más Loco.”

As he’s telling war stories of past canyon races, the trail has suddenly opened on a limitless mesa, with giant standing stones all around and snowcapped mountains in the background. “Wow!” I exclaim.

“I told you,” Caballo says. The mountain air is crisp and pine-scented, and it’s then, as I give in to the euphoric feeling of this perfect mountain morning and cruise along faster than I should, that I understand how he made the transformation from Micah True, oft-injured ultrarunner, to Caballo Blanco, long-ranging roamer of the Sierra Madre mountains.

We’ve hit our four-mile turnaround point, but even though I know it would be foolish for me to try more than eight on my first run at 7,500-foot altitude, it’s so beautiful out here and so fun to lope and bounce along over these trails that I’m reluctant to head back.

Caballo Blanco knows what I mean. “I’ve felt that way for the last 10 years,” he says.

Story Update · December 1, 2016

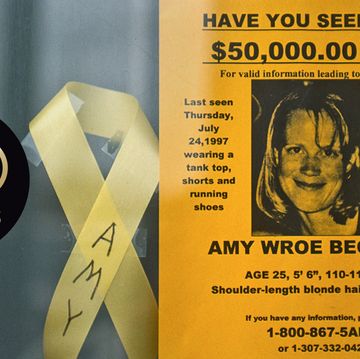

Writer Chris McDougall’s story about the Tarahumara evolved into the 2009 international bestseller Born to Run: A Hidden Tribe, Superathletes, and the Greatest Race the World Has Never Seen. The popularity of the book helped launch the minimalist running boom, inspired by the huarache running sandals worn by the Tarahumara. In 2012, Micah True died while on a run in the New Mexico wilderness (an autopsy revealed heart disease). In 2015, the award-winning documentary Run Free: The True Story of Caballo Blanco premiered with 20 percent of its profits going to True’s nonprofit, Norawas de Rarámuri, which supports the Tarahumara. The Copper Canyon race—since renamed the Ultra Caballo Blanco—was canceled in 2015 because of drug violence in the area, but resumed again this year, drawing 600 runners. Arnulfo Quimare was invited to run the 2016 Boston Marathon; he finished in 3:38, ahead of another Born to Run character, Scott Jurek (who finished in 4:09:27). As documented in Born to Run, Quimare beat Jurek in True’s Copper Canyon ultra in 2006. Jurek triumphed the following year, and still marvels at the ripple effects of this story. “I never really looked at it like this book was going to change my life, change the lives of millions of people, and kickstart an already booming running scene,” he says. “Now, when I look back at it, I think the greatest impact it had was that it made running fun and cool again.” –Nick Weldon