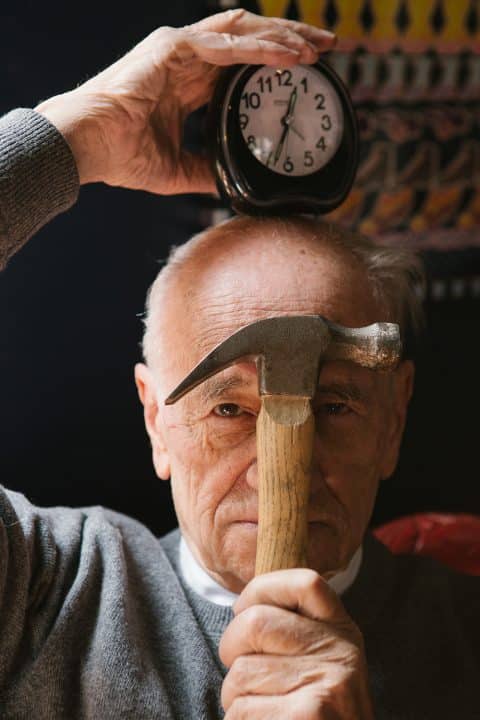

February 16, 2020Legendary artist and designer Pedro Friedeberg is often identified with Surrealism, but the body of work he has created over his six-decade career defies categorization. Of this photo, Friedeberg says, the clock is “a special alarm clock from behind the snake charmer’s institute.” He adds, “The hammer is getting over his sadness at being divorced from Mrs. Russian sickle by order of Khrushchev in 1961.” Top: Various versions of Friedeberg’s famous Hand-Chairs feature prominently in the decor of his Mexico City home.

At first glance, there is nothing especially notable about Pedro Friedeberg’s handsome home, set on a quiet residential side street in Mexico City’s fashionable Colonia Roma neighborhood. But upon closer inspection, you realize that it consists of two houses joined to form one, and a glimpse through a side window reveals a kaleidoscopic assortment of paintings, sculptures and assemblages that is unmistakably Friedeberg.

An avowed eccentric, Friedeberg has, over the course of his 60-year career, produced a prolific and diverse body of work that ranges from furniture design and theatrical sets, to clocks and decorative objects, to sculptures, paintings and works on paper. Although he is widely classified as a Surrealist, his oeuvre follows an arc that defies categorization other than sui generis.

Friedeberg is best known for his iconic Hand-Chair, but as his art-filled home attests, he has also created a galaxy of highly ornamented tables and other furniture with biomorphic legs terminating in human feet, as well as sculptural assemblages, chimeras comprising doll heads, serpents’ bodies and odd elements culled from Egyptian mythology and Hindu symbolism. Many of his pieces display a playful ambiguity between artistic design and functionality. The backs and seats of some chairs are butterflies. Standing mantel clocks have sensuously attenuated legs and feet. Rather than numbers, the clocks’ hour and minute hands point to other hands, stars and moons.

“You are looking into the enfilade of the three blue galleries facing east,” Friedeberg says. “It is in complete change and flux, as it is like a showroom and things keep coming and going. On the left, is a large vitrine with a series of bibelots based on the human hand.”

Friedeberg’s architecturally inspired drawings and paintings portray impossible palaces: structures with innumerable halls and rooms with secret passages and stairs. The vanishing points have vanishing points. Other prints and works on paper depict designs for useless objects with an almost hallucinogenic repetition of elements and dense ornamentation that he refers to as “Nintendo Churrigueresque.” He is represented in major museums and collections throughout the world, including the Musée du Louvre, in Paris; and both the Mexico City and the New York Museum of Modern Art.

In truth, it is nearly impossible to assess the scope of Pedro Friedeberg’s output. His practice seems to be ever-evolving. A vast inventory of paintings, sculpture, furniture and prints resides in his showroom in Mexico City, as well as at Friedeberg Fine Arts (under the direction of his son David), in San Miguel de Allende, and is available through numerous other galleries worldwide.

“The dog is a cross between a xoloitzcuintle and a retriever,” Friedeberg says of this stuffed pup. “She is very old and sleeps all day and most of the night, too. Her name is Dorotea Victoria Eugenia Magda Lupescu. She is mentioned in the Almanach de Gotha, editions of 1988 and 1996. But very briefly.” And the sofa? “The sofa is the napping style. Nothing special.”

Entering Friedeberg’s front foyer is somewhat disorienting: You have the impression of looking at an infinity mirror when, in fact, you are looking through one room into another and, beyond that, into a gallery filled with an abundance of his works. Deeper inside, the house seems to expand from within — a labyrinth that unfolds on three floors, with a staggering array of art and objets displayed throughout.

“This is a room used for cabalistic calculations,” Friedeberg says. “In sacred and profane geometry, there is the maquette for the melancholia mosque reached by a double and triple concentric staircase.” He adds, “The chair is the classical Hand-Chair, but painted in chess squares.”

In another gallery, the foyer experience is reversed, and what appears to be a doorway into an adjoining room turns out to be a reflection in a mirrored wall— an effect that is repeated throughout Friedeberg’s domain, echoing the multi-perspective trompe l’oeil works for which he is celebrated.

Studio manager and curator Alejandro Sordo leads the way upstairs into a library lined with floor-to-ceiling bookcases and more mirrors. There, Friedeberg is busy at work drafting. “I love to talk as I’m working,” he says, happily demonstrating his talent for simultaneously engaging in conversation and executing a complex architectural drawing. All available wall space here, as everywhere in the house, is devoted to framed paintings and prints hung in impressively accurate grids. A sense of precisely ordered chaos reigns. A black-painted human skeleton flecked with gold leaf dangles from the ceiling.

Friedeberg was born on January 11, 1936, in Florence, Italy, the son of German Jews, and escaped with his parents to Mexico three years later. “My mother was very leftist,” says Friedeberg, “but she liked glamour also, having lived in Berlin in the early nineteen thirties. But she didn’t catch that much glamour, she caught more of that cabaret stuff. I think she was very confused and she tried to bring me up confused too, but I knew better what I wanted.”

“I hate the Hand-Chair because it has become an icon and thus a cliché and this is vulgar and dangerous,” Friedeberg says.

Dismissive of accolades, Friedeberg nevertheless received international acclaim for his signature 1962 creation, the Hand-Chair, which appears in his library and seemingly everywhere else throughout the residence in countless variations of scale and finish. “At first, no one took notice,” he says of the piece, which went viral after being prominently featured in Vogue, Architectural Digest and LIFE and championed by legendary decorator David Barrett.

“I felt it was a big mistake,” Friedeberg continues. “Many lives in the twentieth century — many creative lives — are big mistakes. You can create ninety-nine good things and then one bad thing, and the bad thing is what’s appreciated. This is what art is, like everything: fortuitous, accidental, made at the last minute.” To date, 5,000 versions of the Hand-Chair have been sold throughout the world — and that’s not counting the endless knockoffs, easily identifiable by the absence of Friedeberg’s signature, which is burned into the bottom of the genuine article.

“The hands are hand-carved in wood,” Friedeberg says. “The balls are Ping-Pong balls covered in gold leaf.”

Mexico was left-leaning in the late 1930s and ’40s, with less rigid immigration laws than those of the United States, and it became safe harbor for a roster of European émigrés that reads like a who’s who of the avant-garde. When André Breton, cofounder of Surrealism, visited Mexico with his wife in 1938, they stayed with Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. From there, the relationship between the Surrealists on each side of the Atlantic deepened, and by the mid-1940s, European Surrealists like Leonora Carrington (a onetime lover of Max Ernst), Remedios Varo and Alice Rahon (a one-time lover of Pablo Picasso) had made Mexico their home.

“My father wanted me to be an engineer, and I went to a Boston preparatory school for MIT,” says Friedeberg. “But you must contradict your parents if you are a revolutionary and go against them. My parents were minimalists, Bauhaus. I loved Louis XIV, Versailles. I recall a horrendous portrait of Madame Pompadour, fondly. Decadence. Louis XIV was my hero.”

“The two angels in blue underwear are probably eighteenth-century Italian,” Friedeberg says. “They are almost life-size — they were given to me by Jaime Chavez in exchange for a painting of mine in 1983.” As for the busts, he says, “It is a collection started in 1956. I collect them because I can hear them whispering to each other — prayers and dirty jokes and recipes on even-numbered nights in months with the letter R. But not always.”

Friedeberg brought his contrarian spirit to his architecture studies at Mexico City’s prestigious Universidad Iberoamericana in the 1950s, where he broke sharply with the modernism and International Style fashionable at the time. Instead, he favored Baroque and fantastic biomorphic structures, drawing the attention of Mexican Dadaist painter and sculptor Mathias Goeritz, who encouraged him to become an artist. Soon, he had found a perch among Surrealists.

One such construction is often referred to as the Artichoke House, referring to the shape of its roof. Except, Friedeberg points out, “it wasn’t an artichoke. It was a lotus, commissioned by Edward James,” the fabulously rich heir to an American railroad fortune and great patron of the arts, who was reputed to be the illegitimate son of the Prince of Wales. James created Las Pozas, a Surrealist sculpture park in the high mountain town of Xilitla, south of Monterrey, Mexico, and entertained the likes of Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, Man Ray and Luis Buñuel. About the lotus roof of his house, he instructed Friedeberg: “It should close during the day because the sun is so hot, and at night it should open so you can see the stars.” And Breton later declared Friedeberg and Frida Kahlo the only Mexican artists truly part of that movement.

This gallery-style wall includes, according to Friedeberg, “a 1702 print of the city of Magdeburg, Germany, where my maternal family is from, a drawing of Silvia Aguilera, champion tequila drinker” and “a drawing by Picasso, probably a fake.”

Surrealism certainly imbues Friedeberg’s residence, and his formidable collection, with its extraordinary juxtapositions, confirms Breton’s assertion. A carnivalesque array of objets trouvés — Mickey Mouse toys and penny-arcade china figurines — nestles alongside one of Friedeberg’s exquisitely crafted assemblages, a triptych of tiny houses surmounted by pierced arches composed of dice arranged in pyramid form. There are bird cages, a suite of Renaissance Revival furniture upholstered in piebald leather, religious statues of all faiths, top hats, ceramic figurines (one resembling Godzilla), a collection of pre-Columbian Olmec clay heads and countless other pieces. A Leonora Carrington roulette wheel with painted ponies in place of the usual red and black numbers is propped on a Philippe Starck Louis Ghost chair.

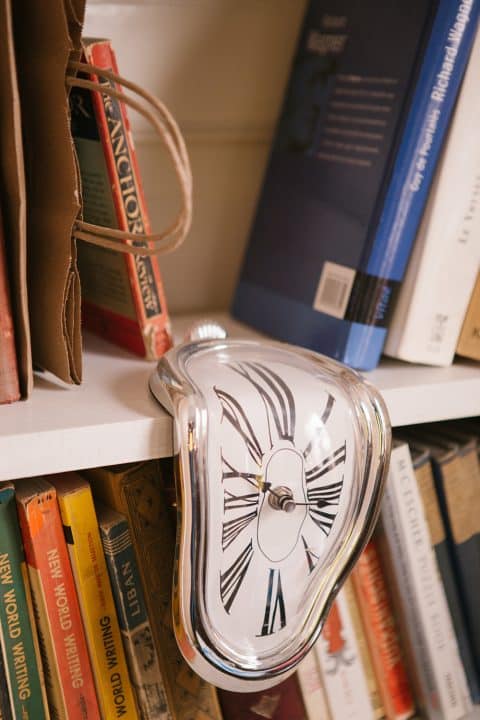

“This is a dime-store replica of Dalí’s clock, inspired by his painting The Persistence of Memory — the second-greatest painting of the twentieth century,” Friedeberg says. “This cheap replica is for sale everywhere.”

Objets d’art are arranged on glass shelves, in vitrines and on every available surface. The house resembles a habitable version of a 19th-century curiosity cabinet. It is a fusion of global cultural influences ranging from ancient Egypt to antique Teotihuacán, Mexico, realized in a chair shaped like the god Anubis or an intricately detailed drawing of a dream palace where Aztec suns intersect with the pyramids at Giza.

An elegantly attenuated and finely crafted giltwood tower conjures the one leaning in Pisa by way of Babylonia. Turn the corner into the stair hall and you are transported into a New England-ish environment with 19th-century portraits and a chest of drawers.

If the modernist credo is less is more, Friedeberg’s mode of decorating could be described as more is more. “I think we should go back to the historical style of our great-grandmothers and -grandfathers, the Victorians,” he says. “They had the right idea. Before they produced Art Deco and Art Nouveau or the Viennese Secession, they would say, ‘Let’s have an Egyptian dining room with a Chinese bathroom and a Louis Quinze boudoir.’ It was much more fun.”

“This is the library and provisional studio, facing south on the first floor,” Friedeberg says. “On the left bookshelf is nothing but poetry — about three hundred volumes — in Spanish, English, Italian, French, German.” He adds, “On the table, unfinished toys and sculptures — works in progress.” Beyond poetry, the shelves also hold numerous reference books, including the 1911 and 1947 editions of the Encyclopedia Brittanica.

While there is nothing new about eclecticism, Friedeberg’s worldview reflects a singular mosaic of aesthetic and cultural influences, including Weimar Germany, the Italian Renaissance and Hinduism, in addition to Aztec, Mayan and other indigenous Latin American civilizations. This multivalent perspective on the world informs his collection as well as his work — and the two are inseparable. His meticulously detailed and technically perfect canvases contain references to Tantric scriptures, Aztec codices, Catholicism and occult symbols.

A top-hatted Friedeberg with a ceramic sun and moon. “I think we should go back to the historical style of our great-grandmothers and -grandfathers, the Victorians,” Friedeberg says. “They had the right idea. Before they produced Art Deco and Art Nouveau or the Viennese Secession, they would say, ‘Let’s have an Egyptian dining room with a Chinese bathroom and a Louis Quinze boudoir.’ It was much more fun.”

Beyond the library is a corridor lined with glass-fronted shelves and cabinets fitted with sliding drawers filled with thousands of rubber stamps. Many are stamps of Friedeberg’s own design that he has used in a variety of ways in his work. “I’ll have to sort them one day,” he says, adding, “The biggest stamp company in Mexico City went broke and I bought them out.” From here, another flight of stairs leads to a studio that evokes a secret room discovered in a dream.

Standing against a mirrored wall is an exuberant Gothic-arched English cabinet bequeathed to Friedeberg by British magic realist painter Bridget Tichenor, who made Mexico her home. “Bridget studied with Paul Cadmus in New York,” he explains. “She worked for Coco Chanel and was a Vogue model. I went to New York with her once or twice, and one time, she said, ‘Oh, let’s go see Philip,’ and I thought, who’s Philip, some hanger-on? And she rang a bell, and we went up forty stories or something, and it was Philip Johnson. They were very close friends from years back.”

As twilight approaches, light rakes across a seven-foot-high Hand-Chair on the terrace, presiding over a view of the neighborhood. The outsize piece is one of an edition of 10. Another crowns the former Mexico City residence of iconic modernist photographers Edward Weston and Tina Modotti.

Despite a marked resurgence of interest in Friedeberg’s creations, he laments, “I feel so very sorry for our civilization, where everything has to change every fifteen years or so: fashion, art, mentality, politics, architecture, food, pets. I admire the Egyptian or the Chinese civilization, where everything lasted, like, five thousand years. And we didn’t have to bother about being à la mode. Fashion is a terrible invention. I mean, it makes money.”

“There are many mirrors in the house,” Friedeberg says. “I am not sure where I am sitting — possibly in the anti-dust-proof salon of distorted memories and disreputable souvenirs.”

Iconoclastic, irreverent, enigmatic — if there is a key to comprehending Friedeberg, it may be the two mirrors in the front foyer infinitely reflecting each other. A passage from the biography on his website reads, “I get up at the crack of noon and, after watering my pirañas, I breakfast off things Corinthian. Later in the day, I partake in an Ionic lunch followed by a Doric nap. On Tuesdays, I sketch a volute or two, and perhaps a pediment, if the mood overtakes me.” Certainly Breton was right.